Laurie Thompson admits she needed to sell her townhouse in Smithville, Ont., fast.

The pandemic had done a number on her finances — the bar where she worked had shut down, twice — and rising interest rates meant her monthly mortgage payments of $2,000 were going to almost double last January. Thompson was facing foreclosure.

“I was desperate,” she told Go Public.

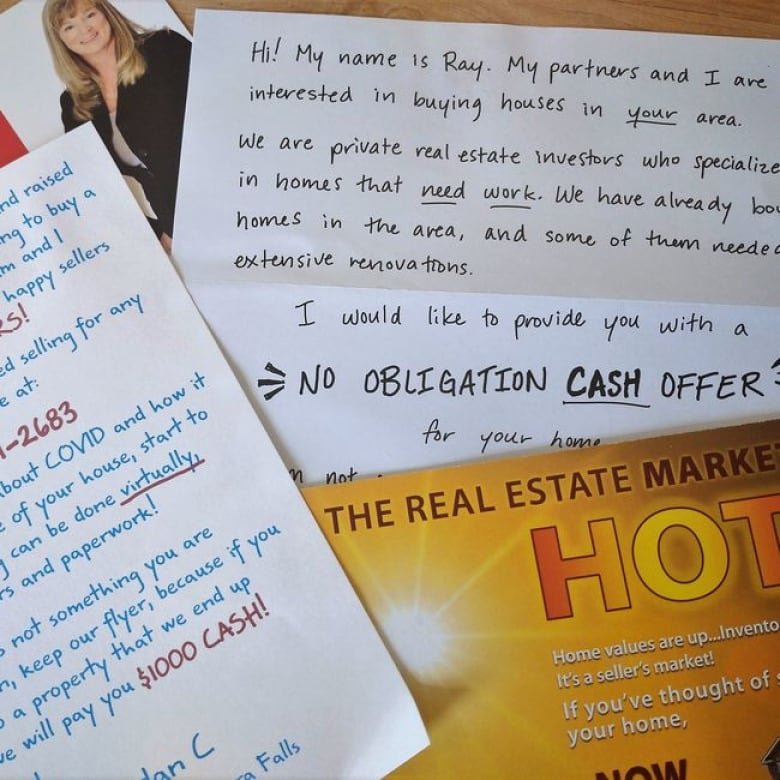

Thompson had seen street signs and posters in her neighbourhood — companies offering to pay quick cash for houses. She’d even received what appeared to be a hand-written flyer in the mail, advertising a hassle-free cash sale — no renovating, open houses, or Realtor commissions.

She hit the internet and found a company with positive reviews and attractive promises called Honest Home Buyers Incorporated (HHBI), based in nearby Hamilton.

- Got a story? Contact Erica and the team at GoPublic@cbc.ca

“The website said, ‘Cash in your hand [quickly],'” said Thompson.

The website promised other advantages, too — “more cash” in a seller’s pocket, a quick closing date, no Realtor fees and it claimed homeowners sometimes get a cheque “the very same day!”

Thompson knew this option meant she wouldn’t be offered top dollar, but figured it was worth getting the house sold, quickly.

“You’re not going to get fair value from a company that’s paying you in 72 hours,” she said. “But … I didn’t want it to sit on the market for three to four months.”

When HHBI owner Mike Chow arrived at Thompson’s townhouse for a walkthrough last January, she told him her employment had been sporadic, the mortgage lender wanted her debt paid off immediately and that she was struggling emotionally — a few months earlier, her partner had unexpectedly died from a heart attack.

Chow produced a contract and offered $575,000. Thompson says she peered over his shoulder as he read through it speedily and encouraged her to sign on the spot.

The whole transaction took about half an hour. Thompson says it likely cost her tens of thousands of dollars in profit, if not more.

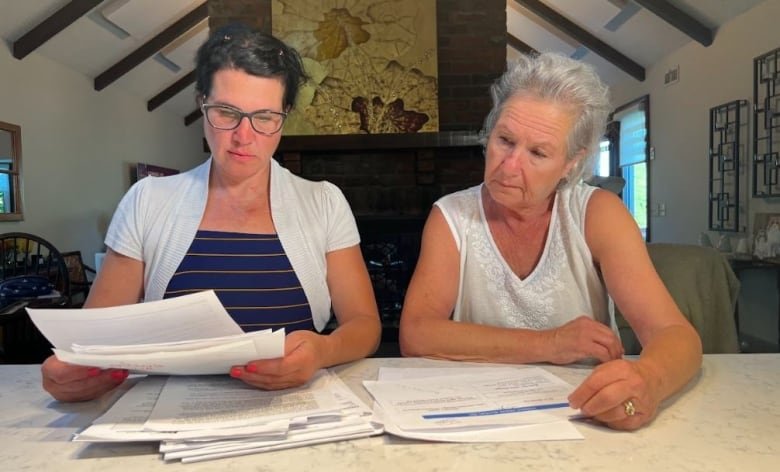

An Ontario woman tells Go Public she’s out thousands of dollars in profits from selling her home through a company offering her fast cash.

An internet search by Go Public found house-buying companies that make cash offers in all provinces and territories. They make similar claims — offering a lifeline to people who’ve suffered a death in the family, are facing foreclosure, divorce or mounting debt.

“It’s clearly preying on people who are desperate and vulnerable,” said housing-market analyst Ben Rabidoux, who dislikes how the contracts lock sellers into terms that cut them out of potential profits.

Rabidoux, lawyers and real estate experts Go Public spoke with all expressed concern that homeowners often don’t understand what a “cash for house” deal actually means — all saying the contracts are often misleading and unethical.

“It’s really gross, but there’s nothing about it that’s illegal,” said Rabidoux.

Chow declined an on-camera interview request, but on the phone said he stands by the transaction. “It’s not like we made her an offer and we didn’t close,” he said.

Unlike real estate agents, cash for houses entrepreneurs are unregulated and have no professional responsibilities to act in the client’s best interest.

Thompson was about to learn that promises of a quick sale at the negotiated price were not going to materialize.

How it works

Her contract was with HHBI, so Thompson figured Chow was the buyer.

“I thought I sold my house to him, right there,” said Thompson. “Done deal.”

But Chow didn’t buy Thompson’s house at all. He secured the option to sell it to someone else before the March 31 closing date — two and a half months later — at a potentially higher price.

It’s called an “assignment” contract — the house can be sold to another buyer before the closing date. In Ontario, and across the country, all residential real estate contracts can be assigned to another buyer unless there’s a clause explicitly stating that isn’t allowed.

“The game here is very clear,” said Rabidoux. “They’re just going to re-market your house … try to sell it somewhere for higher.”

Any profit made on the sale goes into the company’s pocket, not the seller’s — different from licensed real estate agents, who take a commission but leave any profit beyond that for the seller.

Thompson said the fact that the contract could be assigned to another buyer was news to her — there was no language explaining that was allowed.

Some contracts are weighted even more favourably for cash for houses companies, says Rabidoux. They contain a clause that lets the company back out of a deal completely, if no buyer makes an offer by the closing date.

“In most of the [cash for homes] contracts I’ve seen, there’s a lot of wiggle room for the buyer to get out of that contract,” said Rabidoux. “It’s literally, ‘Heads I win, tails I don’t lose.’ It’s a zero-risk business model.”

Growing industry?

There’s no way to officially track how quickly the industry is growing — regulators such as the Real Estate Council of Ontario (RECO) have no jurisdiction over unlicensed entrepreneurs.

Startup costs are so low, says Rabidoux, anyone can get into the industry. He points out that printing up flyers, for example, and getting them into people’s mailboxes only costs a couple of hundred dollars.

“You don’t need any upfront capital,” says Rabidoux. “You need nothing except an ability to blanket a town with thousands of these letters … it’s crazy economics.”

Thompson knew $575,000 was below market value, but says she figured it was worth the trade-off of getting cash fast, without the hassle of numerous open houses.

The next day, though, Chow cancelled the contract and renegotiated for $550,000.

Thompson balked but says she again felt pressured to sign.

Chow explained that Thompson would only be getting a deposit — $7,600 — not the full $550,000. The rest would come when the deal closed, said Chow.

Thompson says he promised that would happen quickly — less than a week, because he had an interested buyer. On the phone with Go Public, Chow admitted he’d claimed to have a buyer, but later said in an email no one “can prove” that.

He had her townhouse listed on MLS, sent in cleaners and a photographer, but Thompson says she thought that was just a formality, on the off-chance the purported buyer fell through.

Instead, agents booked dozens of showings – something Thompson thought a cash for homes deal would avoid.

In an email to Go Public, Chow says he explained the entire process “A-Z” to Thompson, and is unclear why she was confused.

Three weeks later, Chow flipped the house to new buyers, who paid $610,000 – $60,000 more than Thompson’s contract, which he pocketed.

Another promise on the Honest Home Buyers website also turned out to not be as advertised – the claim that “we’re not [real estate] agents.”

Housing market analyst Ben Rabidoux gives tips to ensure a fair deal when selling your home.

Chow’s spouse is Marie Tsai, who is named on HHBI’s website as the company’s office manager, treasurer and bookkeeper. Turns out, she is also a licensed real estate agent and listed Thompson’s property — so made commission.

Thompson filed a complaint with RECO, which eventually penalized Tsai for failing to disclose she had a personal interest in the transaction. She was required to complete a course outlining an agent’s obligations, at her own expense.

Chow said on the phone that his wife being a Realtor was “irrelevant.” Tsai did not respond to an email from Go Public.

Few protections for sellers

Consumer advocate Ken Whitehurst says his office hears from many homeowners who are desperate for relief from high interest rates and other financial pressures.

“People are innocently going on the internet and looking for solutions,” said Whitehurst, executive director of the Consumers Council of Canada.

They often learn too late, he says, that tricky contracts can land them in hot water.

“We expect people to be responsible for their actions, but is that possible when a contract is confusing and people are under pressure?”

With few protections, Rabidoux recommends that people looking to sell their homes go the usual route – use a licensed real estate agent. For people keen to use a company offering cash, he says, take the contract to a lawyer before signing.

“Make sure that what you’re signing is actually what you think it is,” said Rabidoux.

Rabidoux also says provinces need to introduce regulation around assignment contracts, so they can only be used for legitimate reasons – for example, if the buyer loses their job and needs to find someone else to take over the contract.

Chow said there’s always “room for improvement” but says his company has “helped more than any harm we’ve caused.”

As for Thompson, she says she’s speaking out to let others know they should think twice before contacting a “cash for houses” company — no matter how desperate their situation.

“I jumped in with two feet too fast, but I felt like I had to,” she said. “I just feel I was taken advantage of.”

Submit your story ideas

Go Public is an investigative news segment on CBC-TV, radio and the web.

We tell your stories, shed light on wrongdoing and hold the powers that be accountable.

If you have a story in the public interest, or if you’re an insider with information, contact gopublic@cbc.ca with your name, contact information and a brief summary. All emails are confidential until you decide to Go Public.