What’s as big as an alligator, with the body of a millipede, the head of a centipede and the eyestalks of a crab?

That would be Arthropleura, believed to be the largest bug to ever exist. But fear not; it’s been extinct for more 300 million years.

And while we’ve known about these colossal creatures for nearly two centuries, scientists had never found a fossil with its head intact — until now.

“We found the first complete head in a juvenile,” Mickaël Lhéritier, a paleontologist at Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 in France, told As It Happens host Nil Kӧksal.

“We were shocked — really shocked.”

Not only does the discovery paint a more complete picture of this ancient arthropod, from its head to its many, many toes, but it also changes what scientists thought they knew about its modern descendents: centipedes and millipedes.

The findings, by Lhéritier and his colleagues, have been published in the journal Science Advances.

Historic discovery by an undergrad intern

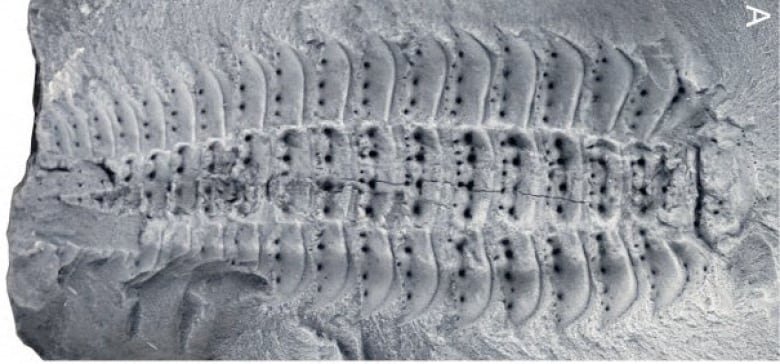

The discoveries hail from two fossils found in a French coal field in the 1980s, preserved in a lump of the solidified mineral.

Once upon a time, scientists would have had to crack it open to find the treasures within, risking further fragmentation. But modern technology means scientists were able to peer inside the fossils using a CT scanner, similar to the kind you might see in a hospital, “but much more powerful,” Lhéritier said.

The discovery was made with the help of undergraduate intern Adrien Buisson.

“He was very happy,” Lhéritier said. “And me as well, of course.”

Scientists have been studying Arthropleura fossils since the first one was discovered in 1854, but the fossils have been incomplete.

“We have been wanting to see what the head of this animal looked like for a really long time,” said James Lamsdell, a paleobiologist at West Virginia University, who was not involved in the study.

That’s because the fossils, found in Europe and North America, have been of shells left behind by Arthropleura after they moulted, squeezing their way out of their exoskeletons as they grew.

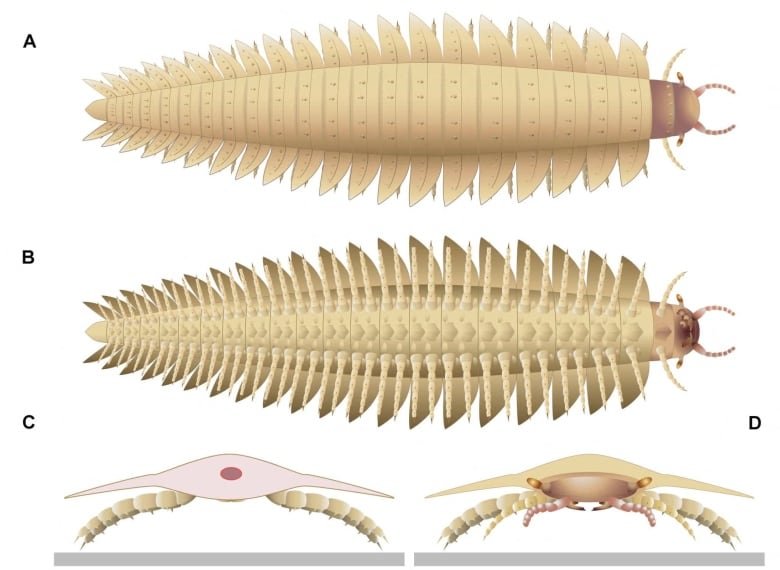

And boy, did they ever grow. It’s estimated Arthropleura could reach about 2.6 metres in length and weigh more than 50 kilograms.

That’s because they roamed — or perhaps skittered — the Earth during the Carboniferous Period, when the planet’s surging atmospheric oxygen levels caused some plants and animals grow to gigantic proportions.

“You also have dragonflies that could reach the size of an eagle, or scorpions that could reach the size of a small dog,” Lhéritier said.

But these newly described fossils are just four centimetres long, because they’re babies.

Lhéritier says if Arthropleura is anything like a modern millipede, the shape of its head likely didn’t change much as it grew, likely to about 20 centimetres in width.

“What we have to find is the head of an adult because we still don’t have one,” Lhéritier said. “It will be interesting to compare the morphology of the adult head and the one of the juvenile.”

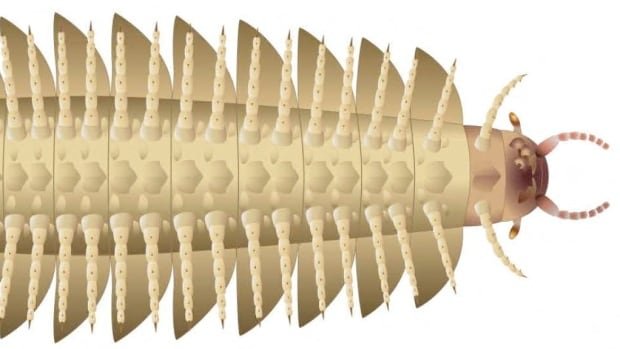

So what did the heads look like? Roughly circular, with slender antennae, stalked eyes and mandibles, which are oral appendages that function as jaws.

“The head of Arthropleura combines features of millipede and centipede,” Lhéritier said. “For example, the antennas are really millipede-like, while the mandibles … are centipede-like. And so this is quite, I would say, striking.”

The study’s authors say this lends new credibility to a controversial theory that millipedes and centipedes are more closely related than previously believed, with Arthropleura as a shared ancestor.

“Millipedes and centipedes are actually each other’s closest relative,” co-author Greg Edgecombe, an expert in ancient invertebrates at the U.K. Natural History Museum, said in a press release.

Based on its mouthparts and a body built for slow locomotion, the researchers suspect Arthropleura was a detritivore like modern millipedes, feeding on decaying plants, rather than a predator like centipedes.

Lhéritier says you can think of it like an elephant or a long-necked dinosaur: “a big animal spending most of his time eating.”

The protruding eyes, Lhéritier says, are also a fascinating find, as they’re usually associated with aquatic crustaceans like shrimps and crabs.

“Millipedes and centipedes didn’t have these kind of eyes,” he said. “And so it is really peculiar.”

Predator or not, not everyone would be keen to spend their time thinking about giant creepy crawlies.

But Lhéritier says he finds Arthropleura, and all arthropods, “fascinating and really cool.”

And as far as he’s concerned, the bigger the better.

“I think they are … magnificent,” he said, “like elephants or whales.”

With files from The Associated Press and Reuters. Interview with Mickaël Lhéritier produced by Leïla Ahouman