There were no F–k Trudeau bumper stickers or flags flying here and there around Alberta when Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s father ran the country a couple generations ago. That may owe more to society’s comparative politeness back then, rather than the intensity of the sentiments.

Because the bitterness lingered for decades beyond Pierre Trudeau’s decision to leave office in 1984.

Despite all his attempts to forge success as a Trudeau out west, the current prime minister resigns as the reviled subject of foul-mouthed flags and political savaging-by-association, and it’s an open question as to how long the seething will last in this second iteration.

Richard Maksymetz remembers door knocking for the federal Liberals in the 1990s in Calgary. “Somebody at every fourth or fifth door would mention the NEP or Trudeau Sr.,” he said, referring to the early-’80s federal policy of oil price controls and revenue sharing that infuriated Alberta and contributed to cratering the region’s economy.

Justin Trudeau wouldn’t have come up at those Calgary doorsteps, he was just a university student in those days. But he certainly understood a thing or two about the residual sentiments out west about his family brand when he entered his dad’s professional field.

A stab in conservative heartland

When he launched his bid for the Liberal leadership in 2012, Trudeau was deliberate about making his first campaign stop in Calgary, at a cultural centre in the city’s northeast.

He was out to plant a party flag in territory that had been hostile to Liberals even before his father’s tenure. And he intended to confront the family legacy head-on.

“I promise you I will never use the wealth of the West as a wedge to gain votes in the East,” he told the partisan crowd.

“It was the wrong way to govern Canada in the past, it is the wrong way today and it will be the wrong way in the future.”

Showing the financial capital of oil country that this Trudeau was his own man with his own ideas and openness to that piece of the western economy appeared important. After becoming leader, he gave a speech to business executives at the Calgary Petroleum Club — to stress the importance of developing energy and natural resources, and marketing them abroad.

Trudeau’s campaign received plenty of advice from pundits and “casual cocktail Liberals” to not bother devoting political resources to places like Edmonton or Calgary, says Dan Arnold, who used to blog as Calgary Grit before becoming the federal Liberals’ lead research strategist and, later, the prime minister’s director of research and advertising.

“Trudeau himself genuinely was committed to a breakthrough in Western Canada,” he said. “And [he] was of the belief that somebody who lives in Calgary, when you’re talking about demographics, values and trends, is a lot more like somebody who lives in a place like Toronto than in rural Alberta.”

In that first run, in 2015, Trudeau’s efforts paid off. The Liberals hadn’t won a single Calgary seat since 1968, the first campaign Pierre Trudeau led; nearly a half-century later, two seats in the city turned red, along with two in Edmonton.

Now, this still wasn’t quite urban-Calgary-as-Toronto; Liberals swept the Ontario capital, while the two pickups in Cowtown came against eight seats that remained Conservative, most of them comfortably so. But Trudeau had created a Liberal beachhead in his rivals’ heartland, and had seemed to exorcise the ghosts of the NEP and his father.

At least temporarily.

Trudeau and Rachel Notley’s NDP both swept into power around the time that oil prices crashed, and along with it, the region’s economy. Both enacted sweeping climate change policies that, to many defenders of the resource sector, became lightning rods.

Trudeau’s musing in 2017 that Canada would “phase out” the oilsands would be brought up by critics for years.

A ban on tanker traffic along part of the B.C. coast was perceived as a direct attack on the fossil fuel sector. A bill overhauling major project approvals was branded the “No More Pipelines Act” by Jason Kenney, the former federal Conservative who’d bid to lead Alberta’s conservative parties.

Kenney had pledged to take the fight to Trudeau, but also repeatedly linked the prime minister to the premier as a “Notley-Trudeau alliance,” an attack line that Premier Danielle Smith has since picked up on.

One province over, Scott Moe picked up that same cudgel as soon as he became Saskatchewan premier in 2018. Talking about his fight against the federal carbon tax, Moe evoked Trudeau Sr.: “Just watch me,” he warned.

In 2019, the Liberals lost all their seats in Alberta and Saskatchewan, but did well enough elsewhere to eke out a minority government.

The quasi-separatist “Wexit” movement cropped up in both provinces after that election, a sign of the intensity of the anger toward the Liberals and Trudeau.

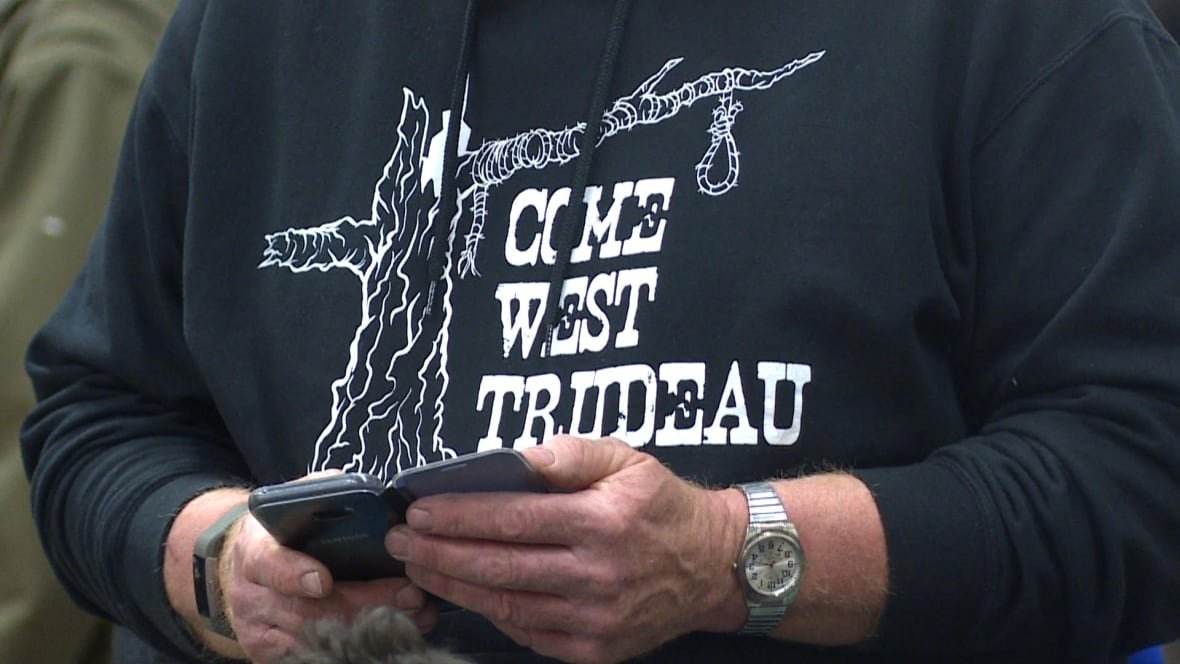

At a Wexit rally in Calgary that fall, one attendee sported a sweatshirt with an empty noose hanging from the end of a tree, and the words: “Come West Trudeau.”

All this fury tended to overlook one of Trudeau’s biggest and costliest gestures toward Alberta and its prime sector: the oil pipeline he’d bought.

The Liberal government had purchased the Trans Mountain expansion pipeline project in 2018, after its Texas-based owner became uncertain of the project’s likelihood of approval amid pushback from climate activists, Indigenous communities and the B.C. government.

It was a multibillion-dollar securing of critical oil infrastructure that would help future expansions and exports from the lucrative, carbon-intensive sector. And Liberals know that they got no political uptick in the area that was helped — but did get the backlash.

“What he did with the TMX pipeline likely hurt him in other parts of the country,” said Arnold, referring to voter anger in parts of more climate-minded urban B.C., Ontario and Quebec.

That was the pipeline the Liberals had approved; but they’d also faced scorn (albeit perhaps not all of it earned) in Alberta for rejecting the Northern Gateway pipeline, and standing by as the Energy East project got scuttled.

The affronts would continue to arrive. Trudeau’s pick of former Greenpeace activist Steven Guilbeault as environment minister in 2021 drew praise in Quebec but ready outrage in Alberta.

Regulations designed to accelerate progress to a net-zero grid got attacked for their threats to the natural gas-fired plants in the West. Oil and gas groups, along with politicians, warned that the emissions cap on their sector amounted to singling them out for carbon reductions and economic harm, atop of all the other climate regulations.

Premier Smith would dredge up the unkind memories of Trudeau’s father — to argue that the son was actually worse.

“I actually preferred the Pierre Trudeau way because he just wanted to steal our wealth. He didn’t want to destroy it. Trudeau, the younger, actually wants to destroy our wealth,” she told podcaster Jordan Peterson last July. “I just can’t imagine how he thinks that is good for the entire country.”

Arnold points out that it wasn’t the intensity of Albertan distaste for Trudeau that forced him out; it was anger rising to unforeseen levels in the rest of the country.

“The Trudeau name became a swear word in most parts of Canada in the past year,” says Erika Barootes, a former UCP president and aide to Smith. “But in the West, it’s kind of like the word ‘Trudeau’ is worse than the ‘c’ word.”

The ‘L’ word (legacy)

But will resentment around the surname hang around in the same way as it did for decades after Pierre Trudeau made his exit?

As Smith and Kenney did with Notley, Smith’s UCP wields attack ads that tie current NDP Leader Naheed Nenshi to Trudeau. But Barootes isn’t sure that a Nenshi-Trudeau alliance tagline can stick around until 2027, when Alberta holds its next election and Trudeau (and perhaps his Liberal government) will be two years gone.

Arnold said he wonders how potent the Justin Trudeau bitterness may be in the West, because there’s no singular policy like the NEP for Albertans and energy workers to focus their furies on.

As for Maksymetz, who rose in the Liberal ranks to organize for Trudeau and became a senior ministerial aide in Ottawa, he suspects the grumbling will never fully go away back home.

“I don’t know if it will be one every four or five doors, but 15 years from now I’m sure people are still going to bring up Justin Trudeau occasionally when a federal Liberal volunteer goes to canvass.”

Nearly a decade ago Justin Trudeau rode a wave of hope and optimism — his so-called “sunny ways” — to the prime minister’s office, leading a once-flailing Liberal party out of the wilderness.

A lot has changed since that time. Not only for Trudeau and his party’s fortunes, but for the world — and how many people feel about the kind of hopeful vision that once helped propel people like Trudeau into power.

Today we’re going to grapple with Trudeau’s legacy, and how he may be remembered: the accomplishments, the failures, the scandals — and whether, as the world transformed around him, Trudeau was able to adapt with it.

Our guests are Aaron Wherry, CBC senior writer and the author of Promise and Peril: Justin Trudeau in Power, and Stephen Maher, author of The Prince: The Turbulent Reign of Justin Trudeau.

For transcripts of Front Burner, please visit: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/frontburner/transcripts [https://www.cbc.ca/radio/frontburner/transcripts]